Introduction: From single-task machines to physical intelligence

For most of its history, robotics has been about specialization. Industrial robots excelled by repeating one carefully programmed motion millions of times. That model is breaking down. A new class of robots is emerging. These are general-purpose systems designed to handle many tasks across changing environments.

This shift mirrors what happened in artificial intelligence with large language models. Instead of building one model per task, researchers now train broad systems that learn general skills first, then adapt. In robotics, this capability is increasingly described as physical intelligence: the ability to perceive the world, reason about it, and act within it using a real body.

Motion capture to drive humanoid robots through complex actions (Image credit: Humanoid)

What changed: the generalist robot

At the center of this transition is the robot foundation model, sometimes called a generalist robot policy. Rather than hard-coding behavior, engineers train a single model across many tasks, environments, and even robot bodies.

Traditional robotics created isolated solutions. Each robot learned one job, using data that could not easily transfer elsewhere. Foundation models replace that fragmentation with shared experience. A single policy can be adapted to new tasks through prompting or fine-tuning, making robots more flexible and less brittle.

The result is not perfection, but range. These systems are better at dealing with variation, ambiguity, and unfamiliar situations—the conditions that define real-world environments.

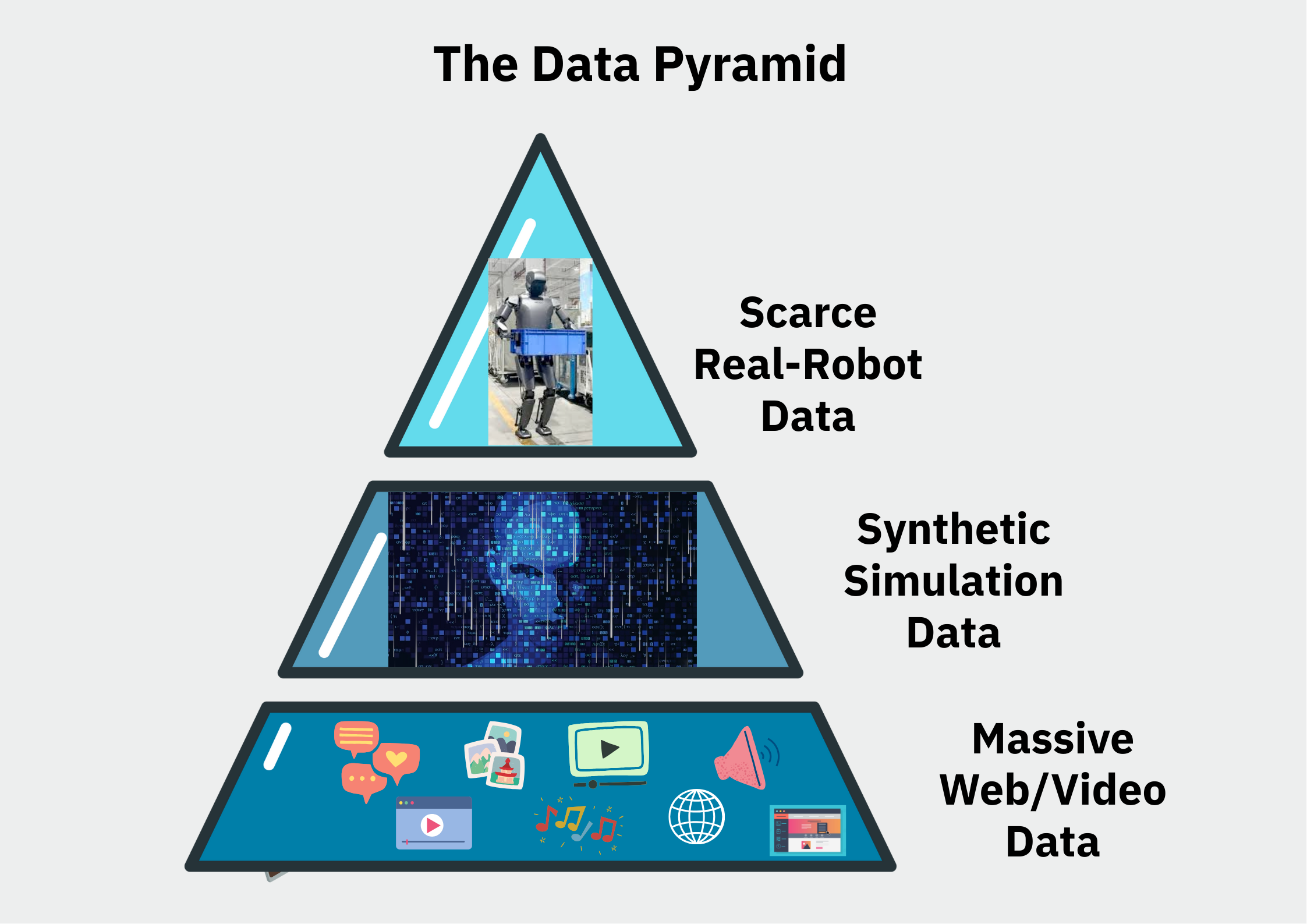

How robots learn: the data pyramid

Generalist robots are trained using a layered data strategy often described as a data pyramid. The idea is simple: teach robots about the world before teaching them how to act in it.

The Data Pyramid

Tier 1: Human and web data Robots absorb broad context by learning from text, images, and video created by people. This gives them an understanding of objects, activities, and everyday cause-and-effect.

Tier 2: Synthetic experience Simulation fills the gap between observation and action. Robots practice tasks in physics-based virtual worlds, where mistakes are cheap and scale is unlimited.

Tier 3: Real-world robot data Finally, robots are refined using real hardware. Human operators guide physical robots through tasks, grounding the model in real friction, contact, and uncertainty.

This layered approach allows robots to generalize without relying entirely on slow and expensive real-world data collection.

What they can do now

With this training stack, robots are beginning to handle tasks that combine perception, planning, and dexterous manipulation. Research demonstrations show robots:

- Bagging groceries and packing mixed objects

- Folding laundry and unloading appliances

- Clearing tables by sorting trash and dishes

- Assembling boxes using both hands and environmental contact

These tasks matter because they are unstructured. They require judgment, not just repetition. While reliability at scale remains an open challenge, the direction of progress is clear.

Strength, agility, and risk

Beyond dexterity, researchers are exploring whole-body control—robots that throw, lift, pull, and balance using coordinated motion. These experiments push the limits of hardware and learning algorithms.

They also highlight risk. Powerful robots operating near people demand predictable behavior, robust safety constraints, and careful evaluation. Issues like simulation shortcuts, reward misalignment, and failure modes during deployment remain active research problems.

Physical intelligence is not just about capability. It is about control.

Why this raises bigger questions

Robots trained on human data inevitably reflect human behavior, priorities, and bias. As they move into workplaces and homes, questions about privacy, accountability, and labor impact become unavoidable.

The core issue is not whether general-purpose humanoids will exist, but how they will be integrated. Regulation, transparency, and human oversight will matter as much as model architecture or hardware design.

Conclusion: capability demands responsibility

General-purpose humanoid robots represent a real shift in how machines interact with the world. Physical intelligence allows robots to move beyond rigid automation and into environments built for people.

That capability brings opportunity—and obligation. The choices made now around data, safety, and deployment will shape how this technology affects work, daily life, and trust in autonomous systems.